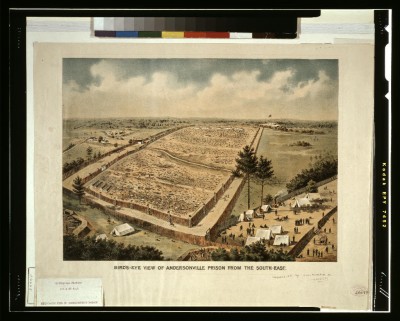

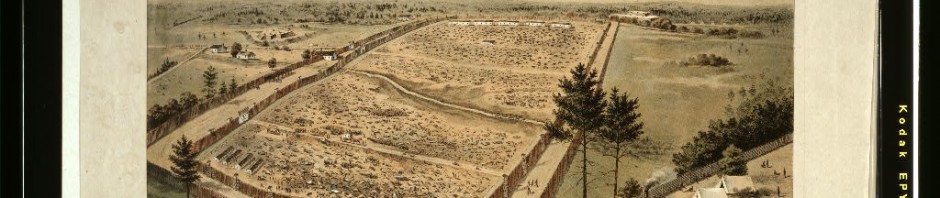

This drawing presents a “bird’s-eye view” of the notorious Andersonville Prison, looking toward the northeast.

This drawing presents a “bird’s-eye view” of the notorious Andersonville Prison, looking toward the northeast.

Amidst all the 150th commemorations and anniversaries of the American Civil War (1861–65), the tragic story of prisoner of war (POW) camps gets neglected—just as the captives themselves were. Reflecting on the brutality and misery, one Civil War historian says almost in disbelief: “We did this to ourselves.” Although true of the entire war, this reflection is particularly haunting in light of what happened “behind the lines” as Americans held Americans captive. More than 410,000 men of the Union and the Confederacy combined were held as prisoners during the war, facing hunger, overcrowding, violence, and disease. About one in seven died.

The prison camp at Andersonville, in southwest Georgia, held the largest number of prisoners. The total number “housed” there topped 45,000. Prisoners were barely sheltered from suffocating summer heat and wintry rains. They lived in the crudest of “tents” or lean-tos, or in barely covered holes in the ground. More than 13,000 Union prisoners died in captivity at Andersonville, a death rate of 29 percent. Death was most commonly due to exposure, disease, and starvation. One Ohio cavalryman commented on his fellow inmates at Andersonville: “It takes 7 of its occupants to make a Shadow.”

The Andersonville National Historic Site has created programs to highlight the experiences of captured soldiers at the infamous prison. Andersonville also now serves as a memorial to all prisoners of war in American history. It is home to the National Prisoner of War Museum. Another resource for learning about prisoners’ experiences during the Civil War is the Virginia Historical Society. The society recently made available online the watercolor paintings by Robert Knox Sneden, a Union private who survived half a year at Andersonville. After being transferred to Camp Lawton, Sneden not only kept an extensive diary; he also made detailed drawings of the prison grounds, some of which he later painted. Present-day archaeologists are making use of Sneden’s drawings of the camp to conduct excavations as they seek to uncover the horrors of prison life during the Civil War.

Image credit: © Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Related Links

- Victory from Within: Exploring the Stories of Prisoners of War

Visit this National Park Service website to learn about the most infamous Civil War prisoner of war camp at Andersonville, Georgia, during the 150th anniversary commemoration.

(Source: National Park Service; accessed October 6, 2014) - A Civil War POW Camp in Watercolor

This website presents the paintings and memoirs of Union soldier Robert Knox Sneden at Andersonville Prison during the Civil War.

(Source: Archaeology.org; accessed October 6, 2014) - Eye of the Storm: The Civil War Drawings of Robert Knox Sneden

This article discusses the life of a Civil War prisoner and the important visual primary sources and diary that are his legacy.

(Source: Virginia Historical Society; accessed October 6, 2014) - “We Did This to Ourselves”: Death and Despair at Civil War Prisons

Reflections on the 150th anniversary of the peak year of suffering in Civil War prisons.

(Source: CNN.com, May 5, 2014)

hi

that’s bad

Dats Not Good

although this is bad we must understand that the men held in these prisons were the men who fought for what they belived in

NUTZ!