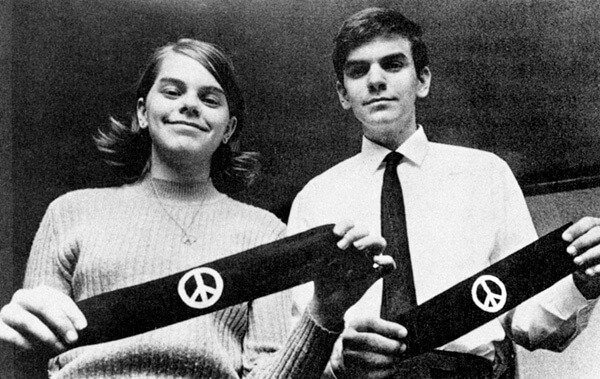

Iconic photograph of Mary Beth and John Tinker showing their peace armbands, 1968

During the early years of American involvement in the Vietnam War, student protests were becoming a common sight across the nation’s college campuses. In high schools, not so much. But one particular student protest in Iowa still, half a century later, carries an important legacy. The case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in February 1969, established a baseline for First Amendment free-expression protections for students in K–12 public schools. In Tinker the Court ruled that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” in the words of Justice Abe Fortas. John Tinker, one of the student co-petitioners in the case, will be the keynote speaker at this year’s We The People National Finals, a civics-related competition centered on understanding constitutional principles. Some 1,200 students and 56 teachers from high schools across the country are expected to participate in the event, sponsored by the Center for Civic Education. (To hear the speech, tune in to the Center’s Facebook page on April 29.)

In 1965, a small number of students in Des Moines, Iowa, planned to wear black armbands to protest and mourn the Vietnam War. School officials learned of the planned protest ahead of time and hurriedly passed a rule banning the wearing of such armbands. The students, among whom were brother and sister John and Mary Beth Tinker, went ahead with their peaceful symbolic expression against the war—and the school suspended them. Aided by the Iowa Civil Liberties Union, the Tinkers sued the school for violating their First Amendment free-speech rights. Although they lost their case in federal district court, they eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, where they prevailed by a 7–2 decision.

Since 1969, because of the Tinker decision, school officials, in order to prohibit any free-speech expression initiated by a student, have had to show reasonable cause that it would result in “substantial disruption” of, or “material interference” in, school activities or infringe on other students’ rights. Tinker has been applied to numerous situations over the past fifty years. The Supreme Court decisions Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser, and Morse v. Frederick in particular have modified Tinker. Some limits have been allowed on students’ expression, such as when it is school-sponsored; if it is considered lewd, vulgar, or plainly offensive; or if it promotes illegal drug use.

Image credit: © GRANGER/GRANGER

Related Links:

- Tinker Turns 50! A Short History of Tinker v. Des Moines

Website of advocacy organization that supports First Amendment rights for students and teachers, founded by one of the co-petitioners in the Tinker v. Des Moines case.

(Source: John F. Tinker Foundation, February 24, 2019) - Tinker after 50: A Historic Ruling Still Relevant after All These Years

Opinion piece by the online education and outreach partner of the Freedom Forum and the Newseum.

(Source: Freedom Forum Institute, January 30, 2019) - The Young Anti-War Activists Who Fought for Free Speech at School

Background on the impact and legacy of the Tinker case.

(Source: Smithsonian, January 23, 2019) - 50th Anniversary of Tinker v. Des Moines Schools Decision

An hour-long presentation and discussion with Mary Beth Tinker and John Tinker, hosted by Iowa Public Television.

(Source: PBS.org, February 22, 2019) - John F. Tinker to Deliver Keynote Address at We the People National Finals

A look at John Tinker, who will keynote the We The People National Finals on April 29.

(Source: Center for Civic Education, March 12, 2019)