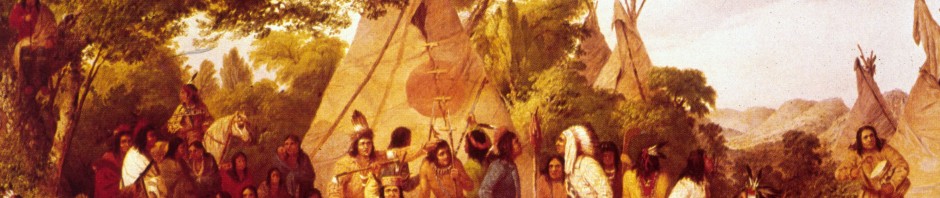

In this painting by Seth Eastman, Dakota Indians perform a traditional dance, the kind of cultural practice studied by ASU researchers Mathew and Perreault.

Two Arizona State University researchers have announced significant findings that bear on the age-old nature-versus-nurture debate. Sarah Mathew and Charles Perreault’s study, based on statistical analysis of extensive data on Native American tribes in western North America, shows that social learning is the most important factor in shaping human behaviors. Their research addresses the question, Do variations in human behavior result from individual adaptations to the varied environments we inhabit or from cultural transmission, such as traditions passed on by our ancestors?

Mathew and Perreault’s answer is squarely on the side of nurture—that is, cultural transmission, or social learning—as the key determinant. Basically, much of what we do, we do because that’s how our parents did it. Although we are “an unusually smart species,” they say, we don’t just figure out on our own how to adapt to different environments. This may seem like a commonsense conclusion, but it actually contrasts with much current thinking in such fields as cognitive science and psychology. The new study is actually the first to directly compare ecological variation and cultural history with a large dataset of societies and behaviors.

The researchers used the Western North American Indian (WNAI) database, a trove of ethnographic data on 172 Native American groups who lived in the North American West prior to contact with Europeans. The behaviors and practices catalogued include technology, kinship systems, marriage and family, economic activities like basket-weaving, and social practices like wedding ceremonies, among others.

Our capacity for social learning from previous generations has its advantages. It promotes the accumulation of information over time. And this helps explain why modern humans have been able to thrive in almost every habitat on Earth as well as why our societies are far more varied than those of any other species. Humans’ reliance on cultural learning, however, can lead to “cultural inertia” (which may sound negative). This finding points to the value of examining why we do many of the things we do—whether eating bread, wearing pants, using surnames, carrying an umbrella when it rains—if we don’t particularly know why we do them.

Image credit: © MPI/Getty Images

Related Links

- How We Were Raised, Not Physical Environment, Explains Human Behavior

Read about the findings of researchers at Arizona State University working on the long-standing “nature versus nurture” question.

(Source: ASU News, June 16, 2015) - Behavioural Variation in 172 Small-Scale Societies Indicates That Social Learning Is the Main Mode of Human Adaptation [Abstract]

Read the abstract of Sarah Mathew and Charles Perreault’s paper published by the Royal Society of London.

(Source: Proceedings B, July 2015) - Study: Social Learning, Not Range of Environments, Best Explains Span of Human Behavior

This article recaps Mathew and Perreault’s findings regarding the dominant role of sociocultural learning in explaining human’s adaptive behaviors.

(Source: Santa Fe Institute, June 17, 2015)